Aortic Valve Stenosis (AVS) and Congenital Defects

What is it?

A valve from the heart to the body that does not properly open and close and may also leak blood. When the blood flowing out from the heart is trapped by a poorly working valve, pressure may build up inside the heart and cause damage.

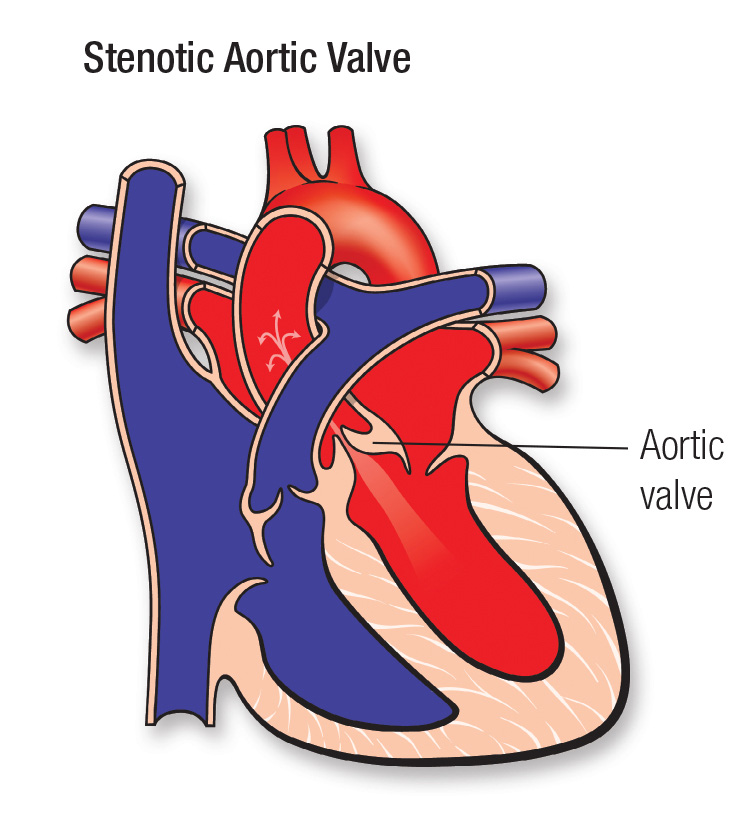

Stenosis (narrowing or obstruction) of the aortic valve makes the left ventricle pump harder to get blood past the blockage.

Insufficiency (also called regurgitation) happens when blood that's just been pumped through the valve leaks backwards into the pumping chamber (left ventricle) while the heart is relaxing.

Aortic stenosis (AS) occurs when the aortic valve didn't form properly. A normal valve has three parts (leaflets or cusps), but a stenotic valve may have only one cusp (unicuspid) or two cusps (bicuspid), which are thick and stiff, rather than thin and flexible.

More information for parents of children with AVS

Some children can have mostly obstruction; others mostly insufficiency. Some children have a valve with both problems.

What causes it?

In most children, the cause isn't known. It's a common type of heart defect. Some children can have other heart defects along with AS.

How does it affect the heart?

In a child with AS, the pressure is much higher than normal in the left pumping chamber (left ventricle) and the heart must work harder to pump blood out into the body arteries. Over time this can cause thickening (hypertrophy) and damage to the overworked heart muscle. In a child with AS, the heart also works harder to pump the normal amount of blood required by the body, and also all the blood that has leaked back into the left ventricle through the valve in between heartbeats. This can cause the left ventricle to be enlarged (dilated) and also may cause damage to the heart muscle.

How does the abnormal aortic valve affect my child?

If the obstruction and leak are mild, the heart won't be overworked and symptoms don't occur. Sometimes stenosis is severe and symptoms occur in infancy. In some children chest pain, unusual tiring, dizziness or fainting may occur. Otherwise, most children with aortic stenosis have no symptoms, and special tests may be needed to determine the severity of the problem.

What can be done about the aortic valve?

The valve can be treated to improve the obstruction and leak, but the valve can't be made normal.

Children with aortic stenosis will need treatment when the pressure in the left ventricle is high (even though there may be no symptoms). In most children the obstruction can be relieved during cardiac catheterization by balloon valvotomy. In this procedure, a special tool, a catheter containing a balloon, is placed across the aortic valve. The balloon is inflated for a short time to stretch open the valve (called a valvotomy).

Some children with stenosis may need surgery. The surgeon may be able to enlarge the valve opening if it's too small. Some valve leakage is likely to develop or increase after a balloon or surgical treatment for obstruction.

If your child's aortic valve no longer responds to valvotomy or has become severely insufficient (leaky), it will probably need to be replaced. The aortic valve can be surgically replaced in three ways:

- The Ross procedure, a surgery in which the abnormal aortic valve is removed and replaced by the child's own pulmonary valve. Then the pulmonary valve is replaced with a preserved donor pulmonary valve.

- Aortic valve replacement with a preserved donor valve.

- Aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve.

Each option has advantages and disadvantages. Discuss them with your child's pediatric cardiologist, cardiac surgeon or both.

What activities can my child do?

If the aortic valve is abnormally formed but has no important obstruction or leak, your child may not need any special precautions regarding physical activities and may be able to participate in normal activities without increased risk. Some children with obstruction, leak or heart muscle abnormalities may have to limit how much they do some kinds of exercise. Check with your child's pediatric cardiologist about this.

What will my child need in the future?

Children with aortic stenosis need lifelong medical follow-up. Your child's pediatric cardiologist will examine periodically to look for problems such as worsening of the obstruction or leak. Even mild stenosis may worsen over time. Also, balloon or surgical relief of a blockage is sometimes incomplete. After treatment the valve keeps working in a mildly abnormal way.

What about preventing endocarditis?

Children with AS and AI risk developing endocarditis. Children who have had their aortic valve replaced will need to take antibiotics before certain dental procedures. See the section on Endocarditis for more information.

Congenital Heart Defect ID sheet (PDF)

More information for adults with AVS

What causes it?

Although some people have aortic stenosis because of a congenital heart defect called a bicuspid aortic valve, this condition more commonly develops during aging as calcium or scarring damages the valve and restricts the amount of blood flowing through.

How does it affect the heart?

Some infants are born with severely narrowed aortic valves need early treatment. However, most bicuspid aortic valves work normally for a long time — sometimes a lifetime. In other patients, the valve can become thick and narrowed/obstructed (stenotic) or curled at the edges and leaky (regurgitant or insufficient). When the valve is obstructed the left ventricle pumps at a higher pressure than normal to push the blood through the narrow opening. In response, the heart muscle gets thicker. When the valve primarily leaks, the ventricle has to pump more blood and the ventricle enlarges.

How does it affect me?

With mild obstruction, patients usually have no symptoms. The problem is detected by the presence of a clicking sound in the heart and a murmur. When the valve opening narrows to about one-fourth its original size, symptoms are common. The most common symptom of an obstructed or leaky aortic valve is shortness of breath with exertion. This usually develops gradually over time, and some patients will just feel "out of shape." Chest pain, lightheadedness or fainting may also occur. Recurrent fevers may indicate the valve is infected.

What if aortic stenosis or regurgitation is still present? Should it be repaired in adulthood?

When the aortic valve becomes excessively obstructed (stenotic) or leaky (regurgitation or insufficiency), the valve must be repaired or replaced.

Repair of the obstructed or narrowed valve can be done 1) in the catheterization lab (referred to as interventional or therapeutic catheterization (PDF)) using a balloon to force the leaflets open; or 2) in the operating room by open-heart surgery. Some valve leakage is likely to develop after either approach. Some patients will have had one or both of these procedures as an infant or child.

Replacing the valve requires open-heart surgery. In most adults, when the valve is no longer working properly, it's best to replace the valve rather than repair it. Deciding when to perform aortic valve surgery and the type of valve to insert are complicated decisions for your doctor. Your aortic valve can be surgically replaced with any of these:

- A mechanical valve made of metal, which requires you to take *blood thinners but is very durable;

- A valve made from biological tissue, which requires no blood thinners but may not last as long and may need to be replaced later;

- A homograft or valve from a donated human heart and preserved in special solutions may be use. Homograft valves require no blood thinners but may not last as long (sometimes this is a good option when a portion of the aorta is also being replaced);

- Your own pulmonary valve (known as the "Ross procedure"), which is then replaced by a preserved donor valve. This requires no blood thinners, and hopefully a more durable aortic valve, although the new pulmonary valve will likely need to be replaced in the future with further surgery.

Each option has advantages and disadvantages. You should discuss them at length with your cardiologist and cardiac surgeon to find the best option for your situation.

Sometimes narrowing is present just below the aortic valve, with or without affecting the valve itself. Then, a more complex surgery, often called a "Konno procedure," may be needed. It will enlarge the part of the left ventricle that leads to the aortic valve. The problem may recur years later, requiring further surgery.

Ongoing Care:

Medical

Everyone with an aortic valve defect needs routine follow-up, whether before or after surgery. Progression occurs over time. Even with the best surgery, the patient is never "cured." The severity of your valve problem will dictate how often you'll need to visit the doctor and how often echocardiograms are needed. Medicines might be useful to lower blood pressure or maintain the health of the left ventricle. You should also consult a cardiologist experienced in caring for adults with congenital heart disease if you are undergoing any type of non-heart surgery or invasive procedure.

Activity Restrictions

If you have a severely obstructed valve, vigorous exercise is not a good idea. Your cardiologist may tell you to limit your activity if this is the case. Ask your cardiologist about your exercise limits. For more information see the Physical Activity and Exercise section.

Endocarditis Prevention

People with even mildly abnormal aortic valves are at risk for bacterial endocarditis. That's why it's important for you to keep your mouth clean and healthy with regular dental check ups. Getting antibiotics before dental procedures isn't proven to be beneficial and so isn't universally recommended any more. But if you have a prosthetic valve, you'll need to take antibiotics before dental work. See the section on Endocarditis for more information.

Problems You May Have

Most patients feel well. Aortic stenosis (obstruction) and insufficiency (leak) usually cause symptoms only when these defects are severe. Symptoms include shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, dizziness, chest pain or occasionally abnormal heart rhythms. Patients may also develop an enlarged aorta over time, which may eventually require surgery. There are usually no symptoms associated with this, which can only be detected with imaging.

Pregnancy

The risk from pregnancy depends on how severely the valve is obstructed or how much it's leaking.

If you have mild or moderate stenosis and your left heart muscle (ventricle) is functioning normally, you can have a safe pregnancy, but you need medical supervision throughout the pregnancy. Sometimes balloon valvuloplasty can be done to relieve symptoms if they occur during pregnancy but only when symptoms can't be controlled by medication and bed rest.

If your stenosis is severe and you have symptoms, avoid conception until you've had your heart valve repaired or replaced. If you're considering pregnancy and you have aortic valve stenosis, you should meet with a multidisciplinary medical team that can give you more information about the risk of pregnancy to you and your baby.

Pregnancy in aortic regurgitation is better tolerated, but if the regurgitation has weakened the heart muscle and signs of heart failure are present before pregnancy, the risk posed by pregnancy is higher.

In patients who have had their heart valve replaced with a metal (mechanical) heart valve, they may be taking warfarin (Coumadin) which can cause risk to the fetus and alternative means of blood thinning may be required. In aortic insufficiency, women may be taking medicines such as ACE inhibitors such as lisinopril (Zestril) or enalapril (Vasotec). These drugs are dangerous to the developing fetus (see the section on Pregnancy) and need to be changed before conception.

It's best to talk with your doctor before you plan to become pregnant.

Will you need more surgery?

If you already had an operation on your aortic valve, chances are high that you may need another. This may be to replace a valve or an enlarging aorta. No surgical fix is ever perfect, so regular follow-up with a doctor who is informed about this particular problem is recommended.