Single Ventricle Defects

What are they?

Rare disorders affecting one lower chamber of the heart. The chamber may be smaller, underdeveloped, or missing a valve.

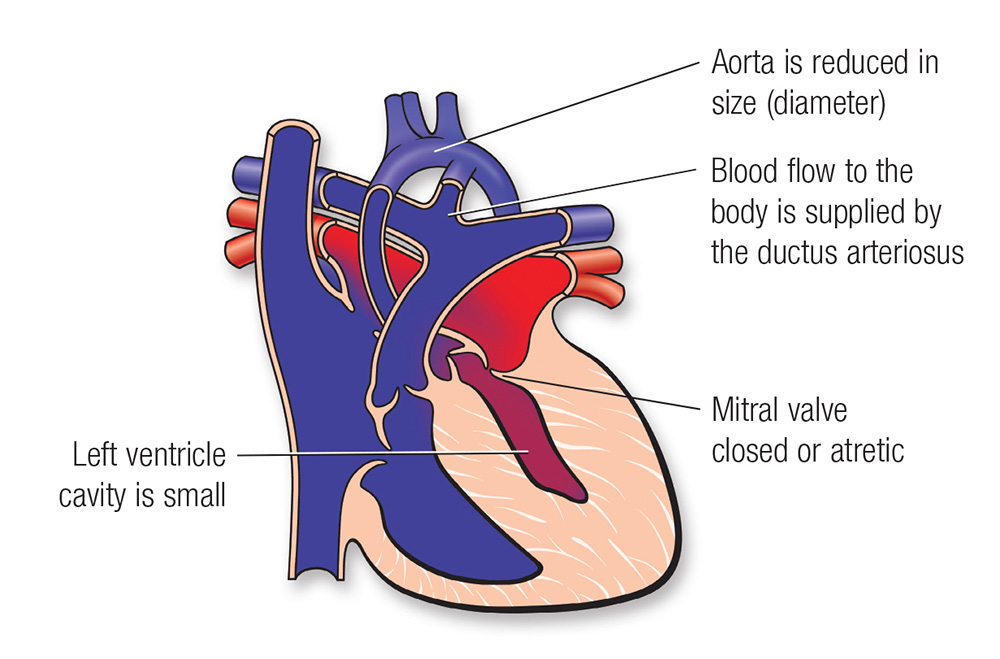

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) - An underdeveloped left side of the heart. The aorta and left ventricle are too small and the holes in the artery and septum did not properly mature and close.

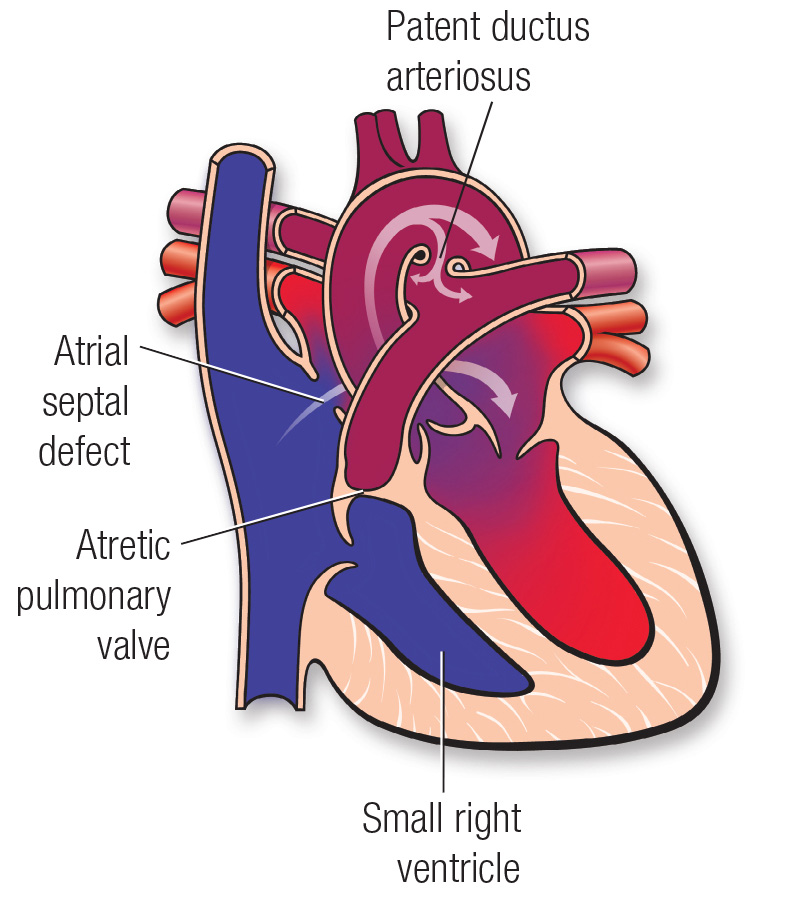

Pulmonary Atresia/Intact Ventricular Septum - The pulmonary valve does not exist, and the only blood receiving oxygen is the blood that is diverted to the lungs through openings that normally close during development.

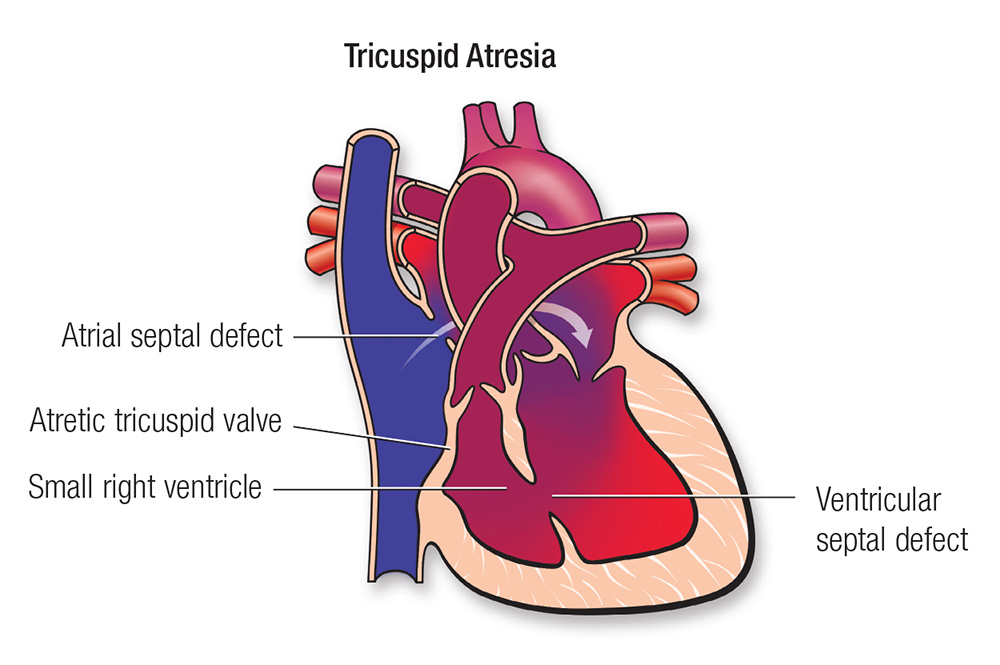

Tricuspid Atresia - There is no tricuspid valve in the heart so blood cannot flow from the body into the heart in the normal way. The blood is not being properly refilled with oxygen so it does not complete the normal cycle of body–heart–lungs–heart–body.

Parents of children with one of these single ventricle defects

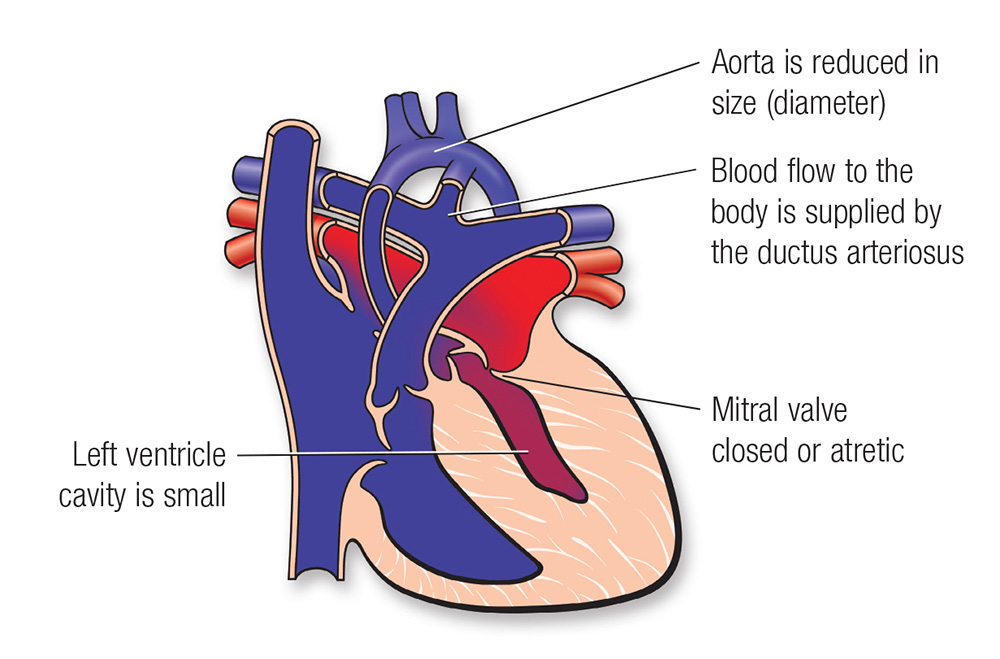

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

What is it?

In hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), the heart's left side — including the aorta, aortic valve, left ventricle and mitral valve — is underdeveloped.

What causes it?

In most children, the cause isn't known. Some children can have other heart defects along with HLHS.

How does it affect the heart?

In HLHS, blood returning from the lungs must flow through an opening in the wall between the atria (atrial septal defect). The right ventricle pumps the blood into the pulmonary artery and blood reaches the aorta through a patent ductus arteriosus (see diagram).

How does the defect affect my child?

The baby often seems normal at birth but comes to medical attention within a few days of birth as the ductus closes. The baby may appear ashen, have rapid and difficult breathing and have difficulty feeding. This heart defect is usually fatal within the first days or month of life unless it's treated.

What can be done about the defect?

Although this defect isn't correctable, some babies can be treated with a series of operations, or heart transplantation. Until an operation is performed, the ductus arteriosus is kept open by intravenous medication. Because these operations are complex and need to be adapted for each child, it's necessary to discuss all the medical and surgical options with your child's doctor.

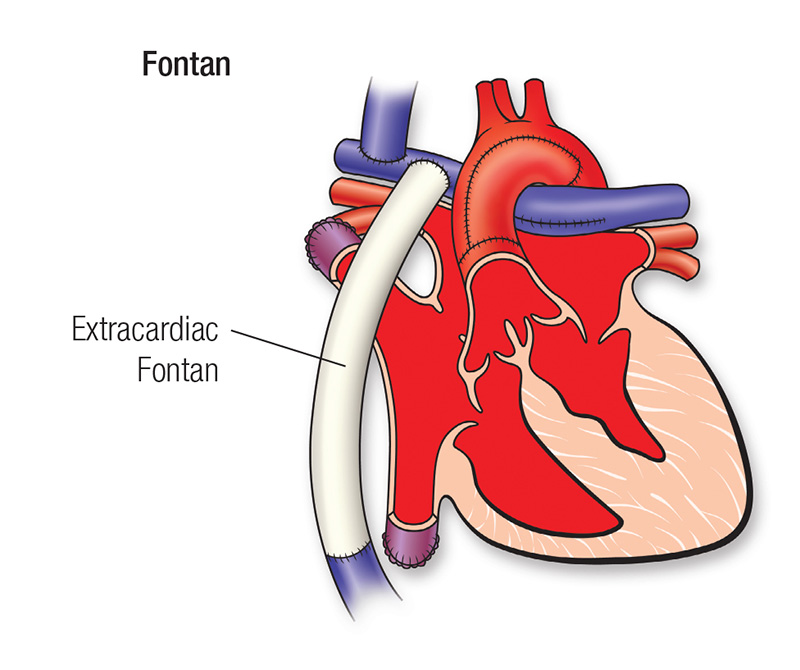

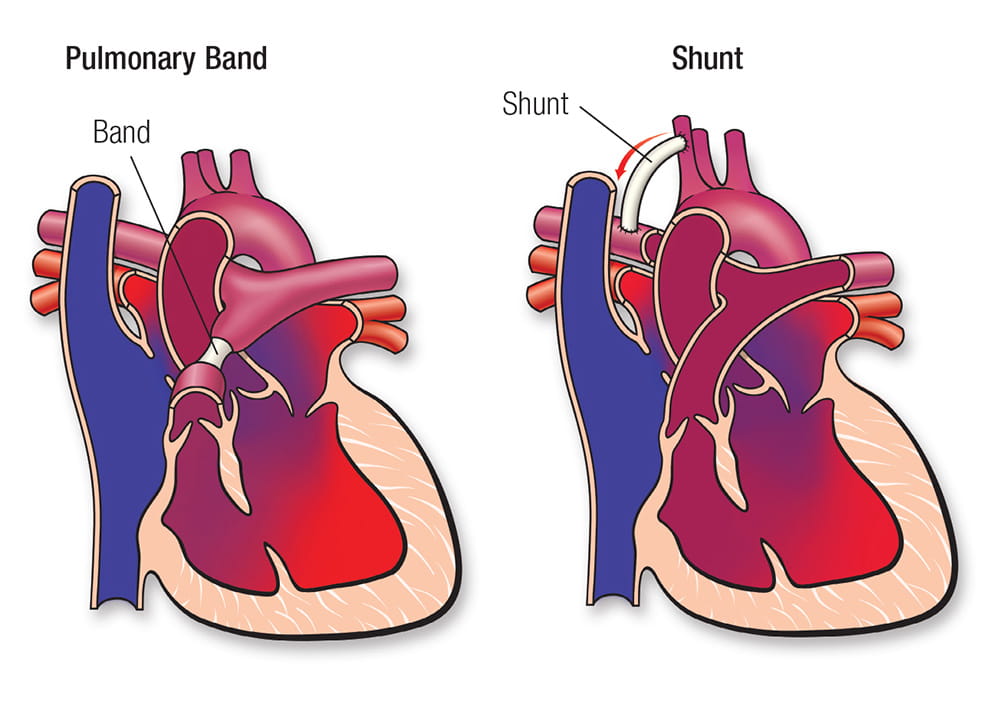

If you and your child's doctor agree that surgery should be performed, it will be done in several stages. The first stage (Norwood procedure) allows the right ventricle to pump blood to both the lungs and the body without the need for the ductus to be kept open. Blood is directed to the lungs through either a Blalock-Taussig (arrow on image below) or Sano shunt. The Norwood procedure must be performed soon after birth. The second stage (bidirectional Glenn or hemi-Fontan) is usually performed between 4 and 8 months and the third stage (lateral tunnel Fontan or extracardiac Fontan) is usually performed between 18 months and 3 years.

These operations create a connection between the veins returning low-oxygen blood to the heart and the pulmonary artery. The goal is to allow the right ventricle to pump only oxygenated blood to the body and to prevent or reduce cyanosis (lower than normal blood oxygen levels). Some infants require several intermediate operations to achieve this.

Some doctors recommend heart transplantation to treat HLHS. Although it can provide the infant with a heart that has normal structure, the infant will require life-long medications to prevent rejection. Many other transplant-related problems can develop, and these should be discussed with your child's doctor.

What activities can my child do?

Children with HLHS may be advised to limit their physical activities to their own endurance. Generally, many competitive sports pose greater risk. Your child's pediatric cardiologist will help determine the proper level of activity.

What will my child need in the future?

Children with HLHS require lifelong follow-up by a cardiologist for repeated checks of how their heart is working. Virtually all children with HLHS will require heart medicines, heart catheterization and additional surgery.

What about preventing endocarditis?

Children with HLHS are at increased risk for developing endocarditis. Ask your pediatric cardiologist about your child's need to take antibiotics before certain dental procedures to help prevent endocarditis. See the section on Endocarditis for more information.

Congenital Heart Defect ID sheet (PDF)(link opens in new window)(link opens in new window)

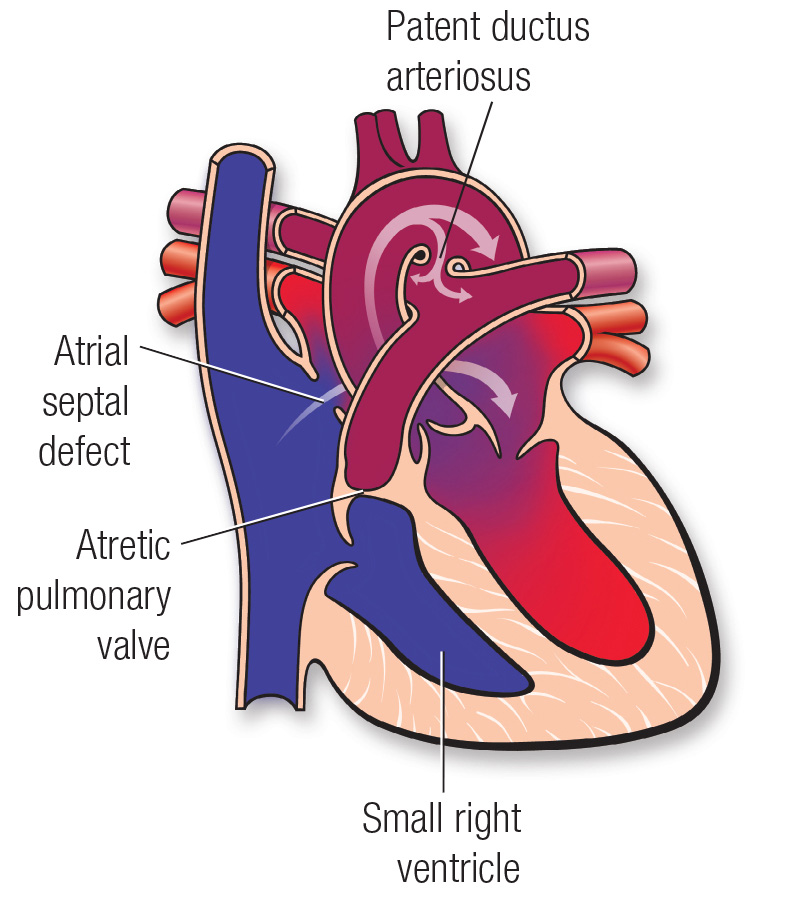

Pulmonary Atresia

What is it?

In pulmonary atresia no pulmonary valve exists. Blood can't flow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery and on to the lungs. The right ventricle and tricuspid valve are often poorly developed.

What causes it?

In most children, the cause isn't known. Some children can have other heart defects along with pulmonary atresia. (Children with tetralogy of Fallot who also have pulmonary atresia may have treatment similar to others with tetralogy of Fallot.)

How does it affect the heart?

An opening in the atrial septum lets blood exit the right atrium, so low-oxygen blood mixes with the oxygen-rich blood in the left atrium. The left ventricle pumps this mixture of oxygen-poor blood into the aorta and out to the body. The infant appears blue (cyanotic) because there's less oxygen in the blood. The only source of lung blood flow is the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), an open passageway between the pulmonary artery and the aorta.

How does pulmonary atresia affect my child?

If the PDA narrows or closes, the lung blood flow is reduced to critically low levels. This can cause very severe cyanosis. Symptoms may develop soon after birth.

What can be done about the defect?

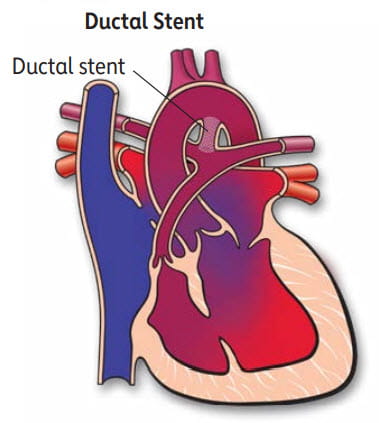

Temporary treatment includes a drug to keep the PDA from closing. To increase blood flow to the lungs, there are two options. A surgeon can create a shunt between the aorta and the pulmonary artery. Alternatively the interventional catheterizer can place a stent in the patent ductus arteriosus to keep it open. A more complete repair depends on the size of the pulmonary artery and right ventricle.

A more complete repair depends on the size of the pulmonary artery and right ventricle. If the pulmonary artery and right ventricle are very small, it may not be possible to correct the defect with surgery. In some children, abnormal channels (sinusoids) form between the coronary arteries and the right ventricle. These sinusoids can also limit the type of surgery a child can have. In children where the pulmonary artery and right ventricle are more normal in size, open-heart surgery may help the heart work better.

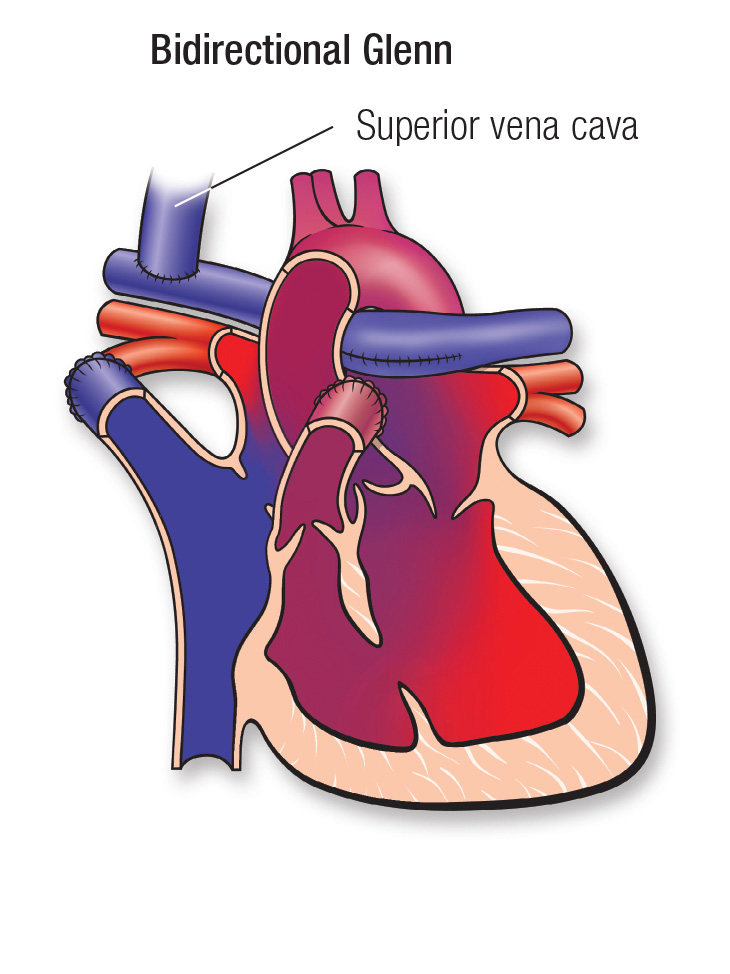

If the right ventricle stays too small to be a good pumping chamber, the surgeon can connect the body veins directly to the pulmonary arteries. The atrial defect also can be closed to relieve the cyanosis. These surgeries are called the Glenn and Fontan procedures.

What activities can my child do?

Children with pulmonary atresia may be advised to limit their physical activities to their own endurance. Some competitive sports may pose greater risk. Your child's pediatric cardiologist will help determine the proper level of activity.

What will my child need in the future?

Children with pulmonary atresia need regular follow-up with a pediatric cardiologist and, once they reach adulthood, lifelong regular follow-up with a cardiologist who's had special training in congenital heart defects. Some children may need medicines, heart catheterization or additional surgery.

What about preventing endocarditis?

Children with pulmonary atresia are at increased risk for developing endocarditis. Ask your pediatric cardiologist about your child's need to take antibiotics before certain dental procedures to help prevent endocarditis. See the section on Endocarditis for more information.

Congenital Heart Defect ID sheet (PDF)

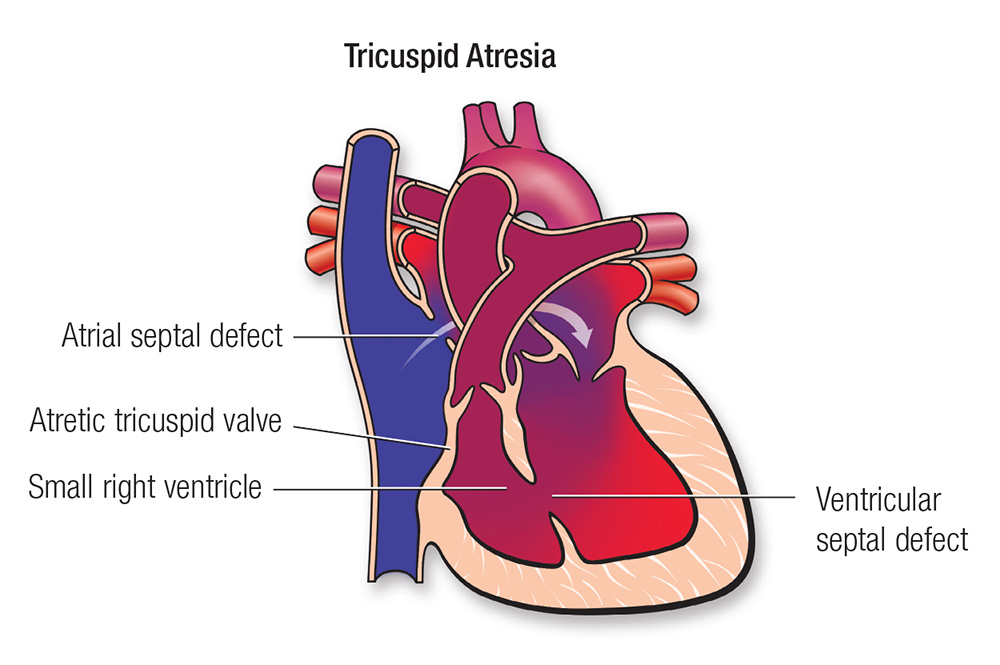

Tricuspid Atresia

What is it?

In this condition there's no tricuspid valve so blood can't flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle. As a result the right ventricle is small and not fully developed. The child's survival depends on there being an opening in the wall between the atria (atrial septal defect) and usually an opening in the wall between the two ventricles (ventricular septal defect). As a result the low-oxygen blood that returns from the body veins to the right atrium flows through the atrial septal defect and into the left atrium. There it mixes with oxygen-rich blood from the lungs. Most of this partially oxygenated blood goes from the left ventricle into the aorta and on to the body. A smaller-than-normal amount flows through the ventricular septal defect into the small right ventricle, through the pulmonary artery, and back to the lungs. Because of this abnormal circulation, the child looks blue (cyanotic).

What can be done to treat it?

It’s often necessary to perform a surgical shunt or a ductal stent to increase blood flow to the lungs. This improves the cyanosis (blue appearance of the skin). Some children with tricuspid atresia have too much blood flowing to the lungs. They may need a different type of surgery, called pulmonary artery banding, to decrease blood flow to the lungs. This is important to protect the lung blood vessels.

Can it be repaired?

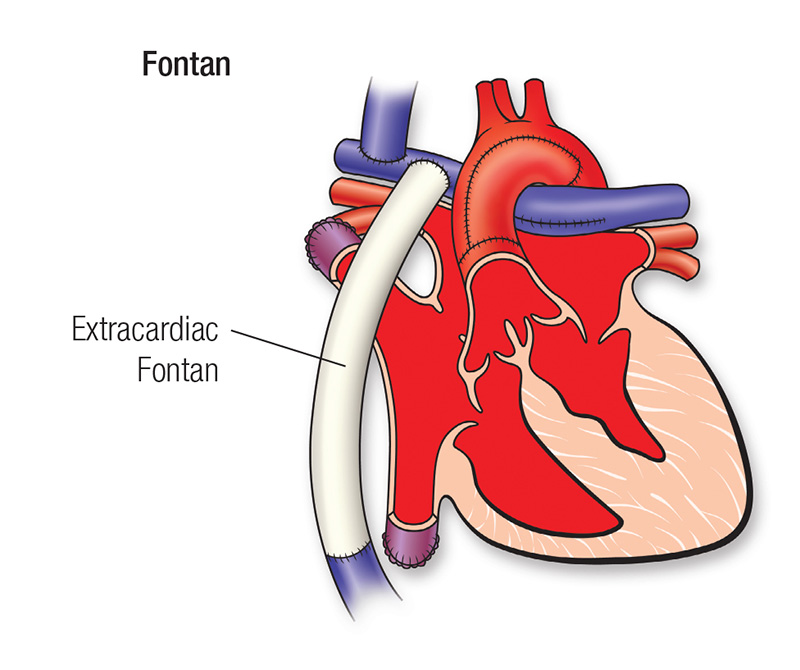

Most children with tricuspid atresia can have surgery to allow their hearts to work more like normal. Connections are created between the body veins and the lung (pulmonary) arteries. This is usually done in two stages. First the large vein from the upper half of the body (the superior vena cava) is connected to the lung arteries in a procedure called a bidirectional Glenn operation.

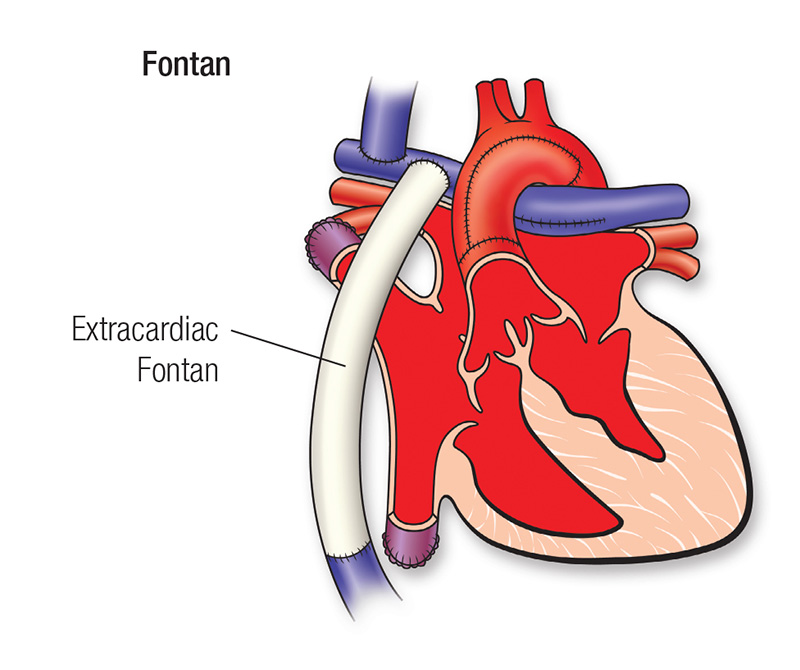

Later the large vein from the lower half of the body (the inferior vena cava) are connected to the lung arteries in a surgery called a Fontan operation. Sometimes, at the time of the Fontan surgery, an opening is purposely left between the low oxygen and high oxygen sides of the blood flow. The Fontan operation may eliminate or greatly improve the cyanosis but, without a right ventricle that works normally, the heart doesn't work like a normal heart, which has two pumps. The Fontan procedure can be performed using a tube that goes around the heart as shown in the picture or with a path (baffle) that goes inside the heart. Both types of Fontan operations route the oxygen-poor blood from the lower half of the body and liver to the lungs.

What will my child need in the future?

Children with tricuspid atresia require lifelong follow-up by a cardiologist for repeated checks of how their heart is working.

What about preventing endocarditis?

Children with tricuspid atresia are at increased risk for developing endocarditis. Ask your pediatric cardiologist about your child's need to take antibiotics before certain dental procedures to help prevent endocarditis. See the section on Endocarditis for more information.

Adults with one of these single ventricle defects

Tricuspid Atresia

In this condition, there's no tricuspid valve so blood can't flow normally from the right atrium to the right ventricle.

As a result, the right ventricle is small and not fully developed. Survival depends on there being an opening in the wall between the atria (atrial septal defect) and usually an opening in the wall between the two ventricles (ventricular septal defect). As a result, the low-oxygen blood that returns from the body veins to the right atrium flows through the atrial septal defect and into the left atrium. There it mixes with oxygen-rich blood from the lungs. Most of this partially oxygenated blood goes from the left ventricle into the aorta and on to the body. A smaller-than-normal amount flows through the ventricular septal defect into the small right ventricle, through the pulmonary artery, and back to the lungs. Because of this abnormal circulation, the patient with this condition looks blue (cyanotic) until surgery can be performed.

Pulmonary Atresia/Intact Ventricular Septum

In pulmonary atresia, no pulmonary valve exists. Blood can't flow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery and on to the lungs. The right ventricle and tricuspid valve are often poorly developed.

An opening in the atrial septum lets blood exit the right atrium, so low-oxygen blood mixes with the oxygen-rich blood in the left atrium. The left ventricle pumps this mixture of oxygen-poor blood into the aorta and out to the body. The infant appears blue (cyanotic) because there's less oxygen in the blood. The only source of lung blood flow is the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), an open passageway between the pulmonary artery and the aorta.

Some patients with pulmonary atresia/intact septum can have a repair that allows the right ventricle to grow and function in a more normal way than other patients with single ventricles. A more complete repair depends on the size of the pulmonary artery and right ventricle. If the pulmonary artery and right ventricle are very small, the patient may require the same type of operation as other single ventricle patients. In some patients, abnormal channels (sinusoids) form between the coronary arteries and the right ventricle. These sinusoids can complicate this condition and even result in a heart transplant being recommended.

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

In hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), the heart's left side — including the aorta, aortic valve, left ventricle and mitral valve — is underdeveloped. Blood returning from the lungs must flow through an opening in the wall between the atria (atrial septal defect). The right ventricle pumps the blood into the pulmonary artery, and blood reaches the aorta through a patent ductus arteriosus.

The series of operations are similar to those done in other patients with single ventricles; however the first operation (Stage I Norwood) is more complicated than for other patients with single ventricles.

What causes a single-ventricle heart defect?

In some cases, a genetic problem may be associated with a single-ventricle heart. Most cases have no identifiable cause.

How does it affect the heart?

Underdevelopment of a ventricle can compromise blood flow to the body in some cases and the lungs in other cases. Without early intervention many patients die in infancy. In a small number of patients, the type of single ventricle results in a balanced circulation between the body and lungs, and survival through childhood is possible without surgery.

How does it affect me?

Almost all adults with single ventricles have had at least one, and in many cases, two or three operations in childhood. Most of these operations result in oxygen-poor blood from the veins going to the lungs without going through a pumping chamber (ventricle) and the ventricle that's present pumping blood to the body. Problems can arise from inefficiency of blood going to and returning from the lungs because of the lack of a pumping chamber to the lungs.

If single ventricle was repaired in childhood, what can I expect?

Surgery is often necessary in the first week of life to increase or decrease blood flow to the lungs. A procedure called a shunt is done to increase blood flow to the lungs in the first week of life. This improves the cyanosis. Some children with tricuspid atresia have too much blood flowing to the lungs. They may need a different type of surgery, called pulmonary artery banding, to decrease blood flow to the lungs. This is important to protect the lung blood vessels. A small number of children have just the right amount of blood going to the lungs and don't need an initial operation.

Almost all adults with single ventricle have also undergone subsequent operations to create connections between the body veins (inferior vena cava and superior vena cava) and the lung (pulmonary) arteries. This is usually done in two stages. First, the large vein from the upper half of the body (the superior vena cava) is connected to the lung arteries in a procedure called a bi-directional Glenn Operation.

Later, the large vein from the lower half of the body (the inferior vena cava,) as well as the veins from the liver, are connected to the lung arteries in a surgery called a Fontan Operation.

Sometimes, at the time of the Fontan surgery, an opening, called a fenestration, is purposely left between the oxygen-poor and oxygen-rich sides of the blood flows. The Fontan operation may eliminate or greatly improve the cyanosis, but without a right ventricle that works normally, the heart doesn't work like a normal heart, which has two pumps.

Problems You May Have

Many patients have survived three to five decades after single ventricle surgery in childhood. Many of these patients are highly functional, with good activity levels. However, some patients with single-ventricle defects do have health problems.

In the few patients in whom surgery has not been performed, there is cyanosis (lower oxygen levels, causing blueness), lower energy and a higher risk of infections such as brain abscess or endocarditis (infection of the heart). These problems shorten the lives of some people.

If you've had surgery for a single-ventricle defect, you can live a relatively normal life. However, your ability to exercise vigorously is usually reduced.

Several basic types of problems are most common in this group of people. These problems may relate to the person's age at the time of the operation and the type of surgery done. Potential problems include:

- Rhythm problems, generally fast heart rate (tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, atrial flutter) or slow heart rate.

- Fluid retention, particularly in the abdomen and lower extremities. Some adults may develop varicose veins after the operation.

- Greater risk of weakening and failing heart muscle when there's only one ventricle.

- Blood clots inside the heart that may require anticoagulation therapy.

Ongoing Care

What will I need in the future?

Single-ventricle defects are among the most complex congenital heart problems. If you have this defect, you'll need regular checkups by cardiologists with expertise in adult congenital heart disease as well as ongoing care all your life. You should also consult a cardiologist with expertise in care of adult congenital heart disease if you're undergoing any type of non-heart surgery or invasive procedure.

Medical

Many people with single-ventricle defects require daily or multiple medications. This care is best given by a cardiologist who's very familiar with the anatomical complexities and complications that these patients have. This requires the expertise of a cardiologist trained in congenital heart disease.

You will need at least yearly checkups to monitor your health. This may mean that you require such tests as an electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart, including transesophageal echocardiograms), cardiac catheterization, Holter and arrhythmia event monitoring, and exercise stress-testing.

Activity Restrictions

You may need to limit your activity, particularly competitive sports. If you have decreased heart function or rhythm disturbances, you may need to limit your activity more. See the Physical Activity section for more information. Your cardiologist will help you determine if you must limit your activities.

Endocarditis Prevention

Antibiotics to prevent endocarditis are needed before certain dental procedures. See the section on Endocarditis for more information.

Pregnancy

Some women who have had a Fontan-type operation can conceive and safely carry a pregnancy to term. The risk increases if the heart muscle is weak, if there is obstruction or clot in the Fontan connection or if there are arrhythmias. If you want to become pregnant, it's important to talk to your cardiologist before conception to find out the risks of pregnancy. It's also important to have a high- risk obstetrician who is experienced in caring for patients with congenital heart defects during pregnancy and delivery. See the section on Pregnancy for more information.

Will You Need More Surgery?

Most single ventricle surgeries are performed in the first two to four years of life and don't require more surgery. If you have any of the complications noted above, you may need to have prior surgical procedures revised. Additional interventions may include closing holes, pacemakers, or repair or replacement of leaky valves. In rare cases, a heart transplant may be considered. Your doctor will explain these possibilities, because each single ventricle has unique features.